What happens if Interstate 94 is removed between St. Paul and Minneapolis?

Our Streets Minneapolis is leading the conversation to rethink I-94 and consider various options.

They point out that the people who live in the corridor are the least likely to own a car and drive along I-94, and yet they are the ones being harmed by the pollution.

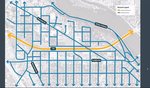

A multi-modal boulevard could fill in the trench with sidewalks and seating, two-way bikeways, a linear park, transitways and stations, traffic lanes, and affordable housing. The existing street grid could be reconnected. A freight alleviation route could move trucks elsewhere.

“I-94 was a very controversial roadway when it was built and it remains very controversial,” said HMC Transportation Chair John Levin during the Hamline Midway Coalition (HMC) Transportation Committee meeting on July 17, 2022, which can be viewed online.

“This project will determine the future of this corridor for the next half century or longer,” said Our Streets Transportation Police Coordinator Alex Burns. It can be hard to consider what the roadway might look like if it wasn’t an interstate. Our Streets seeks to start the community conversation and facilitate the visioning.

“What do we want our community to look like in 20, 50, 100 years?” asked Levin. “How are we going to transition?”

‘A SIGNIFICANT GASH’

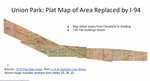

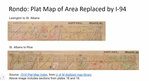

The Minnesota Department of Transportation plans to revamp the 7.5-mile stretch of interstate that links the two Twin Cities from Marion St. west to Hiawatha Ave. It carries about 160,000 cars a day between the two cities. When the roadway was built in the 1960s, it displaced the homes and businesses that were there, as well as the city streets.

The underlying structure of the pavement and bridges is deteriorating, and the normal approach by MnDOT is to reconstruct the entire roadway.

“When MnDOT asked in 2016 if we should think about I-94 differently, the community resoundingly said yes,” stated Levin. “We should not only be thinking about the roadway and the traffic on the roadway. We should be considering the health impacts of the roadway. We should be considering climate change, and the impact of driving on climate change. We should be thinking about equity, not only the historical wrongs but also the future.

“I-94 is a significant gash on the community, and it acts as a barrier,” according to Levin. “It makes access much more difficult.”

Priorities identified in an October 2021 community letter said that the Rethinking I-94 project must repair the highway’s harms and put the needs of adjacent communities first. This includes:

• Reduce air and noise pollution and resulting health disparities

• Advance racial equity and economic opportunity

• Reconnect neighborhoods

• Improve transportation access

• Reduce carbon emissions

• Reduce traffic injuries and deaths

• Prevent displacement

Effect on neighborhoods

“For a lot of us, it feels like I-94 has run through St. Paul forever,” observed Ande Quercus, HMC Transportation Committee member. “St. Paul had a rail transit system for longer than the freeway has been there.”

Rail transit was popular before the automobile industry gained momentum in the 1920s, pointed out Quercus. But the Twin Cities experienced large changes when the interstate system was created.

One in 20 Minneapolis residents lost their home due to highway construction of I-94, I-35 and Highway 55. In St. Paul, 6,000 people were displaced. Black and low-income communities were specifically targeted; 80 percent of Black residents in Minneapolis lived in the neighborhoods where highways were routed, and 80% of St. Paul’s Black population lived in Rondo.

Levin observed that it is important to understand the huge change the freeway had on the neighborhoods it went through. “It was destructive,” said Levin.

28% don’t have a car who live next to I-94

While the freeways enabled many to move out from the cities into the suburbs and still get to work, it didn’t offer the same benefits to all. “Twenty-eight percent of the people in the I-94 corridor don’t have access to a car,” said Levin.

In Minnesota, transportation accounts for one-quarter of greenhouse gas emissions, Levin pointed out. “We will not really be able to address climate change until we address transportation in the region.”

The people who are harmed by I-94 are the ones who use it least, said Burns. Air pollution in the Twin Cities is worse following roadways, particularly the heavily-trafficked interstates. “One of the things that’s really important to know about these urban highways is that the traffic pollution creates these rivers of pollution and poison through the communities through which they run,” said Burns.

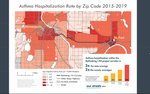

Pollution impacts include asthma, cardiovascular disease, cancer, reduced lung function, impaired lung development, pre-term and low-birthweight infants, childhood leukemia, reduced academic performance in children, dementia and premature death. Some of the city’s highest hospitalization rates for asthma occur along the interstates. Asthma hospitalization within the Rethinking I-94 corridor is three times the state average and two times the county average. It is 9.05 per 10,000 residents.

A look at household income shows that those who live in the Rethinking I-94 corridor make much less than those who live elsewhere. In the corridor, the median household income is $45,164, compared to $57,876 in St. Paul, $62,583 in Minneapolis, $68,871 in Ramsey County, and $82,369 in Hennepin County, according to the American Community Survey.

OTHERS HAVE TAKEN OUT FREEWAYS

Other large cities have converted their highways into boulevards. In San Francisco, the Embarcadero Freeway was ripped out to provide better access to the waterway for residents and tourists. In Seoul, South Korea, the multi-story Cheonggye Freeway was removed to daylight a creek and add a linear park.

The city of Syracuse, N.Y. is set to remove a 1.4-mile stretch of Interstate 81 that has sliced through its downtown since the 1950s. A new community grid will reconnect neighborhoods.

The 11-lane Paris Beltway will be converted by 2030 into an eight-lane system with two lanes for streetcars with a linear park in the center.

Electric cars won’t save us, asserted Burns. It will take decades for mass adoption. Right now, they make up 2% of new car sales and less than 2% of Minnesota cars are electric. They still produce greenhouse gas emissions depending on the grid source. They produce air pollution, create noise pollution, and require metals with harmful mining practices.

Our Streets representatives have knocked on 4,000 doors between Seward and Frogtown neighborhoods. “People don’t believe the state and the city will invest in them and their neighborhoods,” said Raquel Sidie-Wagner. Overall, people have been enthusiastic, said Sidie-Wagner.

“It’s been an overwhelmingly positive experience.

“In the long run, we want to change the way people live and work in the region,” said Levin.

Learn more about the effort to transition I-94 and Bring Back 6th (Highway 55/Olson Memorial Highway) at: twincitiesboulevard.org.

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here